Christina Ostwald and Kelly Whitsell, John R. Oishei Children’s Hospital, Buffalo, NY

Identification of Problem

Blood culture contamination rates in emergency departments (ED) across the United States are as high as 11%, with a range of 1.7%13 to 11%.9

Bacteria found on the skin, also known as common commensals or skin flora, are the culprit of false positive blood cultures (FPBC). FPBC results lead to increased financial costs and unnecessary distress to patients and families. The literature gives a range of values to attribute cost to a FPBC from $100015 to $10,078.6

Hospital cost is related to avoidable admissions, increased lengths of stay, unnecessary antibiotic treatment, and further laboratory investigation to rule out suspected bacteremia. Antibiotic overuse leads to multi-drug resistant organisms that are harder to treat and lead to poor outcomes.

Background

Pediatric patient that present to the emergency department with signs and symptoms of infection may require diagnostic tests that rule out bacteremia and sepsis including a blood culture.

In pediatric patient, it can be challenging even for the most experienced nurse to obtain blood specimens due to patient related factors11 such as: developmental level, ethnicity, size, illness, dehydration, sepsis, and trauma. Mental and emotional status can also be barriers to proper technique.10

Blood cultures are obtained by trained Registered Nurses in the ED. It is imperative for nurses to follow aseptic technique in the process of blood culture collection using the age-appropriate skin decontamination methods, together with allowance for dwell time of the skin preparation. Even with proper aseptic technique, there is the potential for a false positive results due to skin flora.

The microbiology lab provides a list of FPBC every month. The ED Nurse Educator provides targeted 1:1 education for aseptic technique, but this has only led to temporary improvement in the FPBC rate. Retrospective review of FPBC rates in this ED prior to the intervention ranged between 0.45 and 5.63.

PICO

In a Pediatric Emergency Department will the implementation of a novel passive blood diversion device (PBDD) in addition to staff education decrease blood culture contamination rates compared to staff education only?

Review of the Literature

A literature search was conducted using the terms: reduce false-positive blood cultures; contaminated blood cultures; best practice for collection of blood cultures; blood specimen diversion device. This search yielded 702 articles which were then narrowed to include the previous 10 years, peer review only, and the Boolean phrase AND pediatrics and Emergency Department. This advanced search provided 106 articles that were reviewed for inclusion criteria pertinent to the PICO question. Upon completion, 17 articles were included in the literature review including (5) Levell II, (3) Level III and (9) Level V according to the Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence Level and Quality Guide appendix D.12 Due to a majority scoring greater than a level II and zero level 1 articles, this body of evidence suggested that proceeding cautiously with a pilot study and thorough analysis was recommended.

From the sources of evidence found by searching the databases for relevant literature, several reoccurring themes emerged including: false positive blood cultures lead to: unnecessary antibiotic use contributing to antibiotic resistance, increased length of stay, increased diagnostic testing, decreased patient satisfaction, increased overall medical cost.

While there are many published quality improvement studies implementing best practices to reduce false positive blood cultures (FPBC) in adults, literature is lacking on efforts in children. Furthermore, fewer studies address the use of passive blood diversion devices – instruments designed to remove and divert a small volume of blood most likely to contain skin flora and contamination.

Implementation Plan

In the Spring of 2018, a vendor claimed to have a passive blood diversion device (PBDD) product to decrease FPBC rates. The Infection Preventionist (IP) was aware that ED was struggling with a high rate of FPBC rate. Despite diligent educational efforts by the ED to reduce FBPCs, historical data showed the results were not sustained. Current practice involved didactic and hand on education regarding technique to properly prep the skin with age-appropriate disinfection agents, never touching the insertion site after disinfection or tearing the finger off a glove when performing venipuncture. Additional initiatives involved targeted feedback for the individuals involved in the blood draws determined to be FPBCs.

A team was assembled to design a plan to pilot the PBDD in the ED. This involved Infection Prevention, the Emergency Department, and the Value Analysis Team (VAT). The team investigated historical data including costs analysis choosing two months in the summer of 2017, and then implemented the intervention for two months in the summer of 2018, followed by comparison of the data from the intervention.

Infection Prevention reviewed all results for true FPBC based on the Center for Disease Control National Healthcare Safety Network definitions, and used data-mining software for all blood cultures drawn in the ED historically and in the study periods.

Process in the ED for blood specimen collection for pediatric patients is specimen collection from new intravenous (IV) insertion instead of peripheral venipuncture. The vendor provided 400 IV PBDD and the team decided to bundle all the components of the blood draw into readily available kits.

Education for the nurses involved direct 1:1, hands on exposure to the device, review of the blood draw policy, and a vendor created video that was added learning management system. Other components of education included the process for documentation on an exception log when unable to use the device so that follow-up from the nurse manager, educator, and Infection Preventionist could occur. In addition to education, strategies for nurse engagement included creating a sense of excitement around the roll-out with snacks and balloons.

The Finance Department determined the hospital’s actual cost incurred due to a FPBC from 2017 data analysis. Infection Prevention then did a cost analysis of PBDD device implementation vs cost of FPBC. All data was presented to VAT at the hospital and corporate levels.

Conclusions

Feedback on the PBDD was collected on a five question nurse satisfaction survey. The survey provided options to make comments. Overall the nurses found the PBDD to be easy to use (45%) and made sense (85%). Themes identified from the survey included length of tubing was “clumsy, too long, and bulky” with the pediatric patient and “wasting too much blood.” The results were share with the vendor and they modified their product for pediatric patients with shorter tubing which was then implemented in the second study period.

The average cost of FPBCs is both quantifiable and non-quantifiable. After itemizing the hospital related costs, Finance was sought to identify the quantifiable cost of calling a patient back in and/or admission due to the FPBC. Our results ranged from $232 to $6850 which were outliers. Most cases fell between $1500 and $2300 with an average of $1907. Non-quantifiable costs itemized and not considered in our analysis included lost time for the patient and their parents to come back to the hospital, patient satisfaction, staff time for call-backs, physician time/cost, and length of stay in the ED. A cost savings of $71,422 annually was estimated if the PBDD was fully implemented for use with all blood culture draws. It is important to do a cost analysis for each area prior to implementation and the PBDD may prove more cost effective in a high blood culture volume area.

Data collection continued following the intervention period when the device was not available and working its way through the value analysis process. Approval for the device took eight months. Once it was approved, the team repeated the exact study in 2019 for three months using the pediatric modified PBDD with improved nurse satisfaction, decreased return visits and costs, and decreased unnecessary antibiotic use.

Results

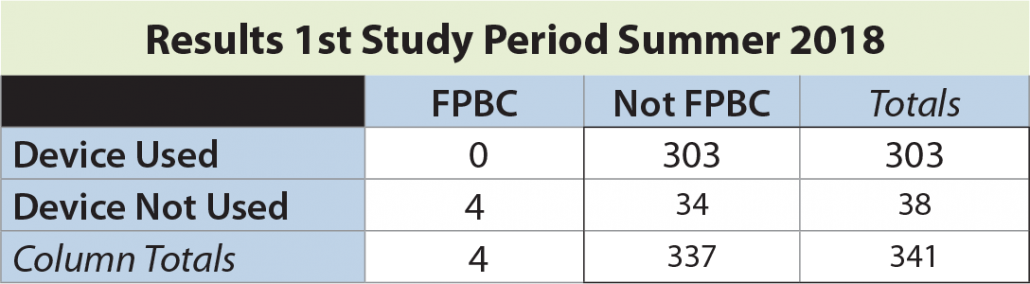

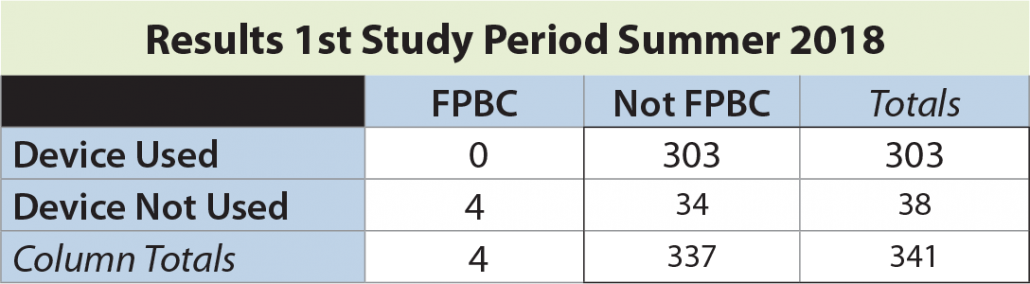

In the first study period, a total of 341 blood cultures were drawn, with an overall FPBC rate of 1.5%. The rate of FPBC when the device not used was 10.5% (4 of 38). No FPBCs were seen in 303 instances when the device was employed (significantly different by Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.0001).

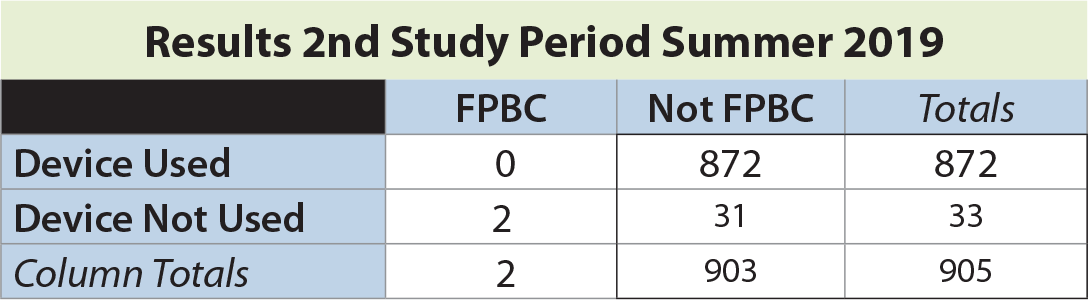

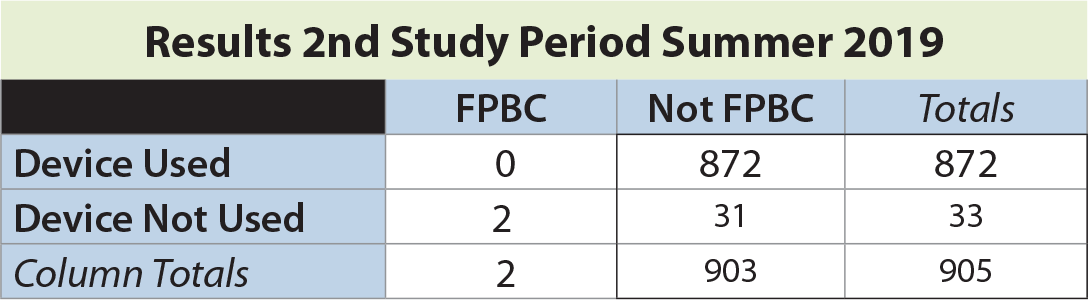

In the second study period, a total of 905 blood cultures were drawn, with an overall FPBC rate of 0.22%. The rate of FPBC when the device not used was 6.06% (2 of 33). No FPBCs were seen in 874 instances when the device was employed (significantly different by Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.0001).

The Fisher exact test statistic value is < 0.0001 ~ The result is significant at p < .01.

This significant reduction in FPBC suggests that employing a passive blood diversion device in addition to education on best practices may decrease FPBCs; return visits in the pediatric ED setting, antibiotics overuse, and overall costs.

Contacts

Christina Ostwald MS RN CIC costwald@kaleidahealth.org

Kelly A. Whitsell MS RN CPEN kwhitsell@kaleidahealth.org

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Jeremy Killson MD, Betty Beyer MS RN, Karl Yu MD, Brian Wrotniak PhD, Pam Trevino PhD RN, & the John R. Oishei ED Nurses.

Download a PDF of this study.

REFERENCES:

1 Bell, M., Bogar, C., Plante, J., Rasmussen, K., & Winters, S. (2018). Effectiveness of a novel specimen collection system in reducing blood culture contamination rates. Journal of Emergency Nursing Online. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jen.2018.03.007

2 Bentley, J., Thakore, S., Muir, L., Baird, A., & Lee, J. (2016). A change of culture: reducing blood culture contamination rates in an Emergency Department. BMJ Open Quality, 5(1), 1-7. u206760-w2754.doi10.1136/bmjquality.u206760.w2754

3 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Healthcare Safety Network. NHSN Organisms List Validation 2018. CDC.gov, Retrieved 7/1/2018.

4 Doern, G. V. (2013). Blood cultures for the detection of bacteremia: U: UpToDate, Calderwood SB ur. UpToDate [Internet]. Waltham, MA: UpToDate, .Retrieved 07/01/2018 from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/blood-cultures-for-the-detection-of-bacteremi

5 Gander, R. M., Byrd, L., DeCrescenzo, M., Hirany, S., Bowen, M., & Baughman, J. (2009). Impact of blood cultures drawn by phlebotomy on contamination rates and health care costs in a hospital emergency department. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 47(4), 1021-1024.

6 Garcia, R. A., Spitzer, E. D., Beaudry, J., Beck, C., Diblasi, R., Gilleeny-Blabac, M., Haugaard, C., Heuschneider, S., Kranz, B.,McLean, K., Morales, K. L., Owens, S., Paciella, M., Torregrosa, E. (2015). Multidisciplinary team review of best practices for collection and handling of blood cultures to determine effective interventions for increasing the yield of true-positive bacteremia, reducing contamination, and eliminating false-positive central line–associated bloodstream infections. American Journal of Infection Control, 43(11), 1222-1237.

7 Garcia, R. A., Spitzer, E. D., Kranz, B., & Barnes, S. (2018). A national survey of interventions and practices in the prevention of blood culture contamination and associated adverse health care events. American Journal of Infection Control, 46(5), 571-576.

8 Gorski LA, Hadaway L, Hagle ME, et al. Infusion therapy standards of practice. Journal of Infusion Nursing (2021); 44 (suppl 1):S1-S224. doi:10.1097/NAN.0000000000000396

9 Hall, R. T., Domenico, H. J., Self, W. H., & Hain, P. D. (2013). Reducing the blood culture contamination rate in a pediatric emergency department and subsequent cost savings. Pediatrics, 131(1), e292-e297.

10 Hall, K. K., & Lyman, J. A. (2006). Updated review of blood culture contamination. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 19(4), 788-802. Retrieved 7/1/2018 from https://cmr.asm.org/content/cmr/19/4/788.full.pdf

11 Kuensting, L.L., DeBoer, S., Holleran, R., Shultz, B., Steinmann, R., Venella, J. (2009) Difficult venous access in children: Taking control. Journal of Emergency Nursing 35(5). 419-424.

13 Marlowe, L., Mistry, R. D., Coffin, S., Leckerman, K. H., McGowan, K. L., Dai, D., Bell, L., & Zaoutis, T. (2010). Blood culture contamination rates after skin antisepsis with chlorhexidine gluconate versus povidone-iodine in a pediatric emergency department. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 31(2), 171-176.

14 McAdam, A. J. (2017). Reducing contamination of blood cultures: Consider costs and clinical benefits. Journal of Emergency Nursing 43(2).126-132

15 Moeller, D. (2017). Eliminating blood culture false positives: Harnessing the power of nursing shared governance. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 43(2), 126-132.

16 Nair, A., Elliott, S., & Mohajer, M. (2017). Knowledge, attitude, and practice of blood culture contamination: A multicenter study. American Journal of Infection Control 45. 547-548.

17 Rupp, M. E., Cavalieri, R. J., Marolf, C., & Lyden, E. (2017). Reduction in blood culture contamination through use of initial specimen diversion device. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 65(2), 201-205

18 Self, W. H., Mickanin, J., Grijalva, C. G., Grant, F. H., Henderson, M. C., Corley, G., … & Paul, B. R. (2014). Reducing blood culture contamination in community hospital emergency departments: A multicenter evaluation of a quality improvement intervention. Academic Emergency Medicine, 21(3), 274-282.

19 Snyder, S. R., Favoretto, A. M., Baetz, R. A., Derzon, J. H., Madison, B. M., Mass, D., Shaw, C., Layfield, C., Vhristenson, R., & Liebow, E. B. (2012). Effectiveness of practices to reduce blood culture contamination: A laboratory medicine best practices systematic review and metaanalysis. Clinical biochemistry, 45(13-14), 999-1011.

20 Weddle, G., Jackson, M.A., & Selvarangen, R., (2011). Reducing blood culture contamination in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatric Emergency Care. 27(3), 179-181.